Madrasa Khan

The Khan Madrasa (theological school) is a peaceful 17th-century Koranic school open to non-Muslim travelers thanks to the tolerant atmosphere Special to Shiraz.

The Khan Madrasa (theological school) is a peaceful 17th-century Koranic school open to non-Muslim travelers thanks to the tolerant atmosphere Special to Shiraz.

A four-Ivan plan and an interior courtyard surrounded by student cells on a double arch structure. The current decoration dates back to the 19th century. Moula -Sadra, the famous philosopher of the Safavid era, taught in this school.

In Koranic schools, apart from theology and Koranic sciences, students learn gnostics and jurisprudence, sharia law, and a preface of Classic philosophy and Platonism besides Islamic philosophy.

Madrasa seems not to be fully active, but you always find some smiling mullah in the courtyard to discuss a subject and ask some questions.

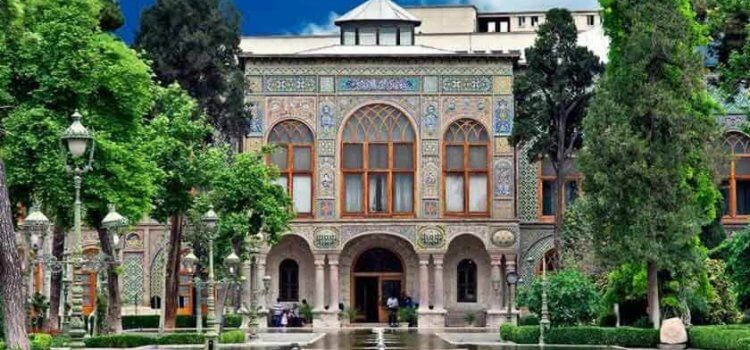

Golestan Palace

Golestan Palace, or the Palace of Flowers, houses some of the capital’s oldest royal buildings and is one of the most prominent historic complexes in Iran.

Golestan Palace, or the Palace of Flowers, houses some of the capital’s oldest royal buildings and is one of the most prominent historic complexes in Iran. During the Qajar rule, this now UNESCO World Heritage site was considered as the political capital of the Qajar dynasty. It witnessed coronations of seven Qajar rulers as well as both of the Pahlavi kings.

As most of the buildings within the site date to the Qajar era, it is generally perceived as a Qajar palace complex. The true history of its origins, however, stretches far back to the Safavid period when, in 1580, Shāh Abbās I built a citadel in Tehran. Later on, between 1760 and 1767, Karim Khan Zand built a divān-khāneh (court or seat of the government) within the Safavid citadel and changed the main design of the complex. At present, only the Marble Throne Veranda and Karim Khāni Nook date to this period.

After Karim Khan’s death, Agha Mohammad Khan, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, took advantage of the ensuing civil unrest in Iran and expanded Qajar territory up to the cities of Tehran and Damghan. In 1795, he defeated the last king of the Zand Dynasty, Lotf Ali Khan, conquered Tehran the following year and declared himself the King of Iran. Aghā Mohammad Khan’s coronation at the Golestan Palace turned it into a place of unrivalled importance among the Qajar kings. Fat’h Ali Shah (1772-1834), who was also crowned here, commissioned further decoration and expansion of the palace complex.

Nāser al-Din Shah, impressed by the palaces he had visited in Europe, had the Palace extensively renovated, having it almost entirely reshaped. The complex did not undergo almost any changes until the fall of the Qajar dynasty in 1925.

Golestan Palace has subsequently witnessed coronations of the Pahlavi kings. During the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, all the surrounding buildings known as andaruni or haramsara (domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the palace and are inaccessible to adult males except for close relations) were completely demolished. These andaruni spaces, known as Farah-ābād during the reign of Fat’h Ali Shah, consisted of several interconnected, exquisite yards surrounded by rooms of various sizes intended for female dwellers of the royal harem who would spend their allocated time with the monarch here. There have always been numerous stories surrounding the haramsara, as told by the favorite wives of the kings, or stories about the famous clown Aziz al-Soltan or the coquetries of Babri Khan, the royal cat whose sudden disappearance made the residents of haramsara melancholic.

Salam Hall (Audience Hall) or Museum Hall

As a passionate collector of unique pieces of art, Naser al-Din Shah converted the Salam Hall into a royal museum, so the valuable gifts from European officials could be kept there.

As a passionate collector of unique pieces of art, Naser al-Din Shah converted the Salam Hall into a royal museum, so the valuable gifts from European officials could be kept there. He also ordered the demolition of Emarat-e Biruni (outdoor mansion), which had previously been used as the palace museum. The hall, nonetheless, continued to be used for the coronation of some Qajar kings and several royal receptions. The Salam Hall is also adorned with large, attractive chandeliers and eye-catching paintings by Kamäl al-Molk. To celebrate the coronation of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the objects on display in this hall were rearranged to what it looks like today.

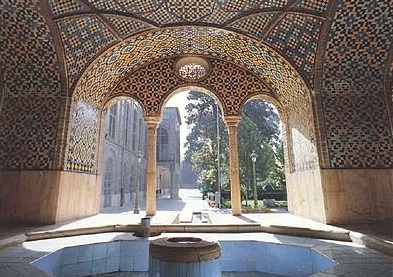

Karim Khani Nook

Next to the Marble Throne Veranda, there is the second Zand monument, the Karim Khani Nook or Karim Khani Veranda which was Naser al-Din Shah’s favorite place of retreat, where he spent long hours in solitude.

Next to the Marble Throne Veranda, there is the second Zand monument, the Karim Khani Nook or Karim Khani Veranda which was Naser al-Din Shah’s favorite place of retreat, where he spent long hours in solitude. When looking at its earlier photos, the veranda has, alas, lost some of its original features. The stairway leading to the Karim Khani Nook has a tragic story of its own. Out of long-nurtured hate for Karim Khan, Agha Mohammad Khan had the Zand monarch’s body disinterred and reburied under the stairway. Later in 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi ordered for Karim Khan’s bones to be reburied next to the Safavid King, Shah Soltan Hosein, in Qom. Some historians insist, however, that the remains were brought back to the Karim Khan Zand’S original grave in Shiraz.

One of the most interesting objects in the Karim Khani Nook is the tombstone of Naser al-Din Shah, assassinated in 1896. Brought here from the Shah Abdol Azim Shrine, it is a single piece of marble stone, bearing a life-like relief of the king carved by Abbas Gholi. More interesting, however, is the story, or rather stories, about the king’s assassination.

One common version among various divergent versions is that on April 29, 1896 Naser al-Din Shih attended the Shah Abdol Azim Shrine in Rey for prayer. Unlike other occasions, however, he ordered for the shrine to be kept open to the public. A man known as Mir-za Reza Kermani, taking advantage of this situation and bearing a petition in his hand, approached the king to ask for his favor. Once at the right distance, he pulled out a handgun and shot the king in the heart. In an attempt to save Naser al-Din Shah, a chair was brought from the private tomb of Badr family, which he was seated on. Faded traces of the king’s blood are still visible on the chair, placed in a corner of the main hall of the palace for the visitors to have a look at.

The rumor has it that in order to avoid any social unrest following the king’s death, it was decided to keep Naser al-Din Shah’s murder secret. The dead body of the king was, thus, placed into the royal coach (now kept in the National Car Museum of Iran) and sent to the Golestan Palace. However, in addition to the corpse of Shah-e Shahid (the Martyr King), there was another man in the couch who impersonated Naser al-Din Shah. Wearing white gloves, he would at times wave at people or touch his moustache in the same way as the dead king used to do. Once in the Golestan Palace, the body of the dead king was buried for a period of one year in the Royal Tekiyeh and later moved to the Abdol Azim Shrine.

Marble Throne Veranda

In 1792, when Aghā Mohammad Khan conquered Shiraz, he had the paintings, curtains, mirrors, and marble slabs from Karim Khan’s citadel in Shiraz transferred to Tehran

In 1792, when Aghā Mohammad Khan conquered Shiraz, he had the paintings, curtains, mirrors, and marble slabs from Karim Khan’s citadel in Shiraz transferred to Tehran, which at that time already had a Zand divan-khāneh, and installed in the Marble Throne Veranda, built in 1807. The veranda contains elements from both Zand and Qajar periods.

In 1807, Fat’h Ali Shah ordered construction of a marble throne, which came to be known as Takht.e Tavous (the Peacock Throne), consisting in total of 65 pieces of marble brought from mines in Yazd, to be placed permanently in the veranda. Designed by Mirza Baba Shirazi (Naqqāsh Bāshi) and the stonecutter, Mohammad Ebrahim Esfahani, this 250-year-old throne was completed in four years, from 1747 to 1751. The jewel-studded throne is carried on the shoulders of angels and demons, referring to the story of Solomon’s flying throne. This is why the Peacock Throne is also called the Throne of Solomon. Seventeen verses on its upper side praise Fat’h Ali Shah and the throne itself.

The Marble Throne Veranda was used on ceremonial occasions and for royal receptions. During religious celebrations and other festivals, the king would sit on the throne while statesmen, royal courtiers, ambassadors and foreign envoys would pay him homage. In 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi held a symbolic coronation in the Marble Throne Veranda before his official crowning.

Jameh Abbasi Mosque (Imam Mosque)

On the Southern wing of the magnificent Naghsh-e Jahan Square, there stands a grand mosque, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which represents one of the greatest achievements of the Safavid period in terms of architecture, decorative arts and the social and religious role it played in its heyday. This unique marvel is nothing but Jame Abbasi Mosque, also known as Shah Mosque and Soltani (Royal) Mosque. After the Islamic Revolution of Iran (1978-79), following the new political sensibilities of the time, it was renamed Imam Mosque.

Shah Abbas Orders the Construction of Jame Abbasi Mosque

Eskandar Beik Turkaman, the great historian of Shah Abbas’ court, tells the story of the construction of Jame Abbasi Mosque as follows: At the beginning of this blessed year (that is, 1611) the astrologists determined the fortunate hour to construct a grand mosque which would be the pride of heaven and earth. And so, the king ordered the construction of the first congregational mosque built under Safavid royal patronage. Even as a sign of God’s approval, several marble mines were discovered nearby, hidden in the depth of earth where no human would have suspected their existence.

Therefore, the construction of Shah Mosque began on the Southern side of Naghsh-e Jahan Square. Actually, the positioning of the mosque was a very clever move. Being located just across Qeysaria Bazaar, it attracted large groups of people who were after their daily business in the bazaar. In addition, passing Ali-Qapu Palace and the theological school and mosque of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque assured people od Safavid protection and patronage. The construction of the mosque which began in 1611 ended in 1629.

However, there are inscriptions in the mosque which indicate several parts or decorations were added to the mosque during the reign of Shah Safi (1629-1642), Shah Abbas II (1632-1666) and Shah Soleyman (1648-1694).

What to See in Jameh Abbasi Mosque (Imam Mosque)

The massive Jameh Abbasi Mosque, covering an area about 19.000 square meters, is an architectural wonder with many details that would bewilder its visitors. In the rest of this article, we would introduce all the necessary details you need to know to fully appreciate the beauties of Jame Abbasi Mosque.

The Splendid Architecture of Jame Abbasi Mosque

The Portal

When you reach Jame Abbasi Mosque, before getting to the portal, you have to pass through a semi-circle pish-khan or forecourt. Flanking the eastern and western sides of the forecourt, there are two corridors containing shops and connected to Qeysarie Bazaar. In the middle of the pish-khan, there is a stone pond which used to be filled with water for the purpose of ablution. The walls surrounding the forecourt are decorated with false-arches, inscriptions, and haft-rangi (seven-color) tiles.

The portal itself is composed of different parts. It includes two goldasta minarets, each one rising as high as 42m. The minarets include decorations of spiral blue turquoise tiles and Bannai inscriptions. At the top of each minaret, there is a goldasta, a special space from which mo’azen calls people to prayer. However, since these goldastas overlooked the royal harem, they were never used during the Safavid period.

The main part of the portal is 27m high, embellished with haft-rangi tiles and faience mosaic. Around the portal, there is a large inscription representing a line from the Quran which reads as: “Do not stand in it ever! A mosque founded on God-wariness from the [very] first day is worthier that you stand in it [for prayer]. Therein are men who love to keep pure, and Allah loves those who keep pure.”

The niche composing the middle part of the portal is decorated with amazing honey-comb stalactites, giving the portal a stunning view. Below the stalactites, in the middle elevation and left and right sides, there are designs of three pairs of peacocks, representing god’s perfection as well as integrity and beauty.

Below this niche, in the middle of the portal, there are several important inscriptions. The largest one, running from East to West, states that Shah Abbas I built Jame Abbasi Mosque from the royal treasure (khāleseh) and dedicated it to the soul of his grandfather, Shah Tahmāsb. At the end of this inscription, you can find the name of the calligrapher, Ali-Reza abbasi, the chief librarian and the master calligrapher of Shah Abbas’ time, and also the date of the completion of the portal, 1616 AC.

Just under the inscription mentioned above, there is another smaller inscription written by Mohammad-Reza Imāmi which credits Moheb-Ali Beig Lala with supervision over the construction of the mosque. This same dignitary had joined the Shah by contributing to the endowments of the mosque from his own personal funds. The names of two architects are also associated with mosque: 1. Maestro Ali-Akbar Isfahani as the engineer of the mosque and, 2. Maestro Badi’-al-Zaman Tuni Yazdi, responsible for procuring the land and construction resources.

At the base of the portal, there exists two high-relief marble vases from which rises spiral turquoise tiles. The spiral tiles, on the one hand, symbolize Tuba tree of paradise, and on the other hand, draw the viewer’s eyes upward toward the apex and infinity.

The original doors of the portal (4 m by 1.7 m each) were of plane trees, covered with a thin layer of gold and silver and decorated with carvings and filigrees. Several lines of poetry are engraved around the door, the last one of them functioning as a chronogram. Based on this line, the gates were installed during the reign of Shah Safi (1629-1642).

A Great Engineering Dilemma Solved

Just like Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, the façade of Jame Abbasi Mosque had to remain flush with the southern side of Naghsh-e Jahan Square, while at the same time orienting its mihrab(s) (prayer niches) correctly toward Qilba or Mecca. And this created a quite difficult challenge for the visual effect of skewed internal axis, which would be magnified in the royal mosque. However, as Sunan Babaie argues: “the architects and patrons of the mosque exploited this very potential for theatrical visual impact by creating a crescendo of forms heaped from one side to the other; viewed from a distance in the Meydān, as would have been the case for most denizens busy in the public square, the eye of the beholder is lead from the open-armed portal composition with its massive pištāq and soaring goldasta minarets to increasingly volumetric and loftier units culminating with the pišṭāq-dome-minarets of the qebla wall. To the worshipper entering the mosque, the transition from the gorgeously tiled and moqarnas-covered ayvān on the Meydān side to the courtyard is mediated through a twisted passageway-cum-ayvān that serves also as the northern ayvān of the courtyard.”

And she continues: “This entrance complex corrects the alignment of the mosque by twisting the axis of approach, but it also provides a liminal space passage through which provides the worshipper the opportunity, visually and spatially mediated, to leave the mundane world behind before entering the sanctified space of the mosque.”

Upon Entering Jame Abbasi Mosque

As the visitor passes through the gate and enters the mosque, he or she finds him/herself in the vestibule of the mosque, with a roof covered with amazing moqarnas (stalactite) decorations. The vestibule is flanked by two corridors, covered with haft-rangi tiles whose densely floral and vegetal decorations are reminiscent of the mythic Persian gardens and the Paradise.

If you take the left corridor, before reaching the main courtyard, you will notice a small door on your left. Passing through this door, you will find yourself in a semi-dark space which is called Gāv-Chāh. In this part of the mosque, there is a quite large pond and above it, on a stone platform, there is water well. Since they used to draw water from these wells by cows, it is called Gav (cow) Chāh (well). The water drawn from the well filled the pond and was used for making ablutions or other sanitary purposes.

The Main Courtyard

Leaving the corridor, you will find yourself in the main courtyard of the mosque. Following the traditional plan of Iranian mosques, known as Chahar-iwany, the main courtyard is surrounded by four iwans or porches. Traditionally, each of these four porches were used in a specific season, providing prayers with suitably warm or cold praying rooms.

In the middle of the courtyard, there exists also a large stone pond which provided prayers with a further source of water for ablution.

By the way, the most important iwan or porch of the mosque is its southern one. Why? Well, the southern porch of the mosque is the one which is oriented toward Mecca, and therefore should be the most decorated and glorious one of the porches. And don’t forget that it is the general pattern in all the Iranian mosques because of the location of Qibla or Mecca.

The Glorious Iwan (porch) of Jame Abbasi Mosque

Well, the southern iwan of Jame Abbasi Mosque is flanked by a pair of minarets, each one soaring as high as 48 m. Through this porch, one can enter the main dome chamber of the mosque.

The main dome chamber is connected to two hypostyles, with amazingly decorated high-rise vaults supported by stone columns. Actually, the columns are made of blocks of stone joined together by molten-lead. This engineering trick increased the flexibility of the mosques and thus the mosques resistance against probable earthquakes.

The Amazing Dome Chamber of Jame Abbasi Mosque

The most significant part of the southern iwan; that is, its dome chamber, is 22.5 m in diameter hemmed by walls as thick as 4.5 m. These thick walls lay the foundation for the turquoise high-rise double-layered dome of the mosque, the one you can also see from outside of the mosque.

The 52m heart-shaped external dome is built over an internal 38m hyperbolical dome, with a 13 m gap between them.

One of the most interesting points about this dome is the way it reflects the sound. Stand under the dome (specially at its center marked by a black stone) and make a sound. You would be surprised how unbelievably it echoes.

The beauty of the mihrab (prayer niche) is enhanced by a marble pulpit with 12 stairs a few meters to its right.

The Theological Schools of Jameh Abbasi Mosque

On the east and west of Jameh Abbasi Mosque, there are two theological schools called Naserieh and soleymanieh. These schools were built during the Safavid period, but an inscription in Naserieh schools indicates that it was rebuilt during the Naser al-Din Shah Qajar and so its name.

In the Suleymanieh School, there is a sundial, indicating the exact time of noon all throughout the year. This unassuming engineering wonder, which looks like a simple step, was built by Sheikh Baha al-Din Mohammad Ameli, known as Sheikh Bahai, the Safavid polymath who was involved in the design of the whole monument.

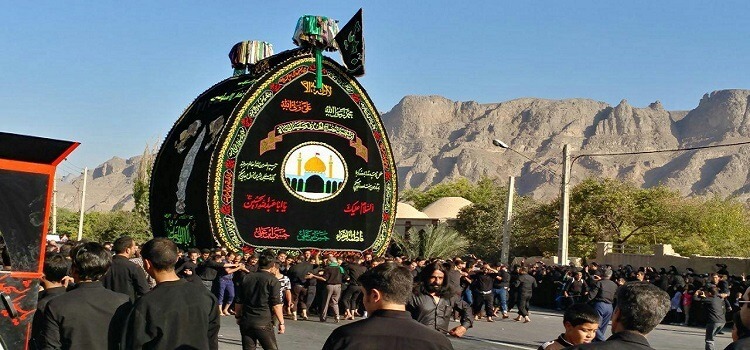

Nakhl

Nakhl is a tall wooden object and because of its resemblance to the date palm tree, is known Nakhl among Iranians.

Nakhl

Nakhl is a tall wooden object and because of its resemblance to the date palm tree, is known Nakhl among Iranians. Now that you have learned the name of our bizarre object, you may be wondering what this Nakhl is good for?

As Peter Chelkowski explains, Nakhl is described as a wooden bridal pavilion, decorated with mirrors, lanterns, precious pieces of cloth and silk shawls. Sometimes, flowers and green branches are also added to Nakhl for decoration. Furthermore, it is also described as a bier to which swords, daggers, mirrors and valuable fabrics are attached.

Mostly, Nakhls are used in a ritual ceremony called Nakhl-Gardani (carrying Nakhls) in the procession of Ashura, the 10th day of the Arabic month of Muharram when Imam Hussain was killed in Karbala by the troops of Yazid, the second Caliph of the Omayyid Caliphate. Actually, the nakhl is a symbol of Imam Hussein’s coffin, carried around during his mourning ceremonies.

If you pay careful attention, Nakhl also bears a resemblance to the cypress tree, the symbol of beauty in Iran, and thus representing the beauty of Imam Hussein. The daggers and swords attached to the nakh represent the objects by which Imam Hussein was wounded and killed. In addition, mirror decorations attached to the nakhl reflect light, turning it into a glittering object, signifying the shining aura of Imam Hussein’s corpse. Mirrors reflecting the mourners also gratify their wish of identification with their wronged Imam.

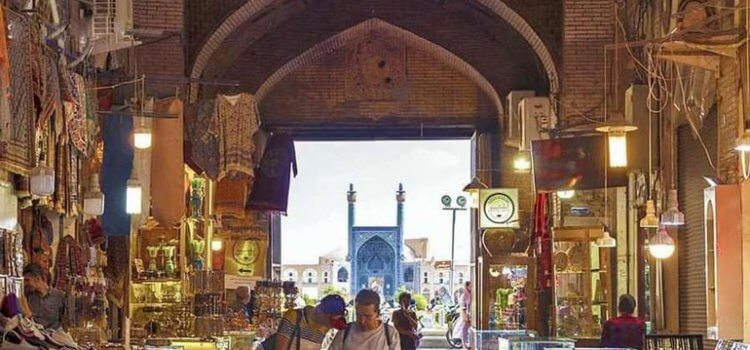

Qeysarie Bazaar

Qeysarie Bazaar, also known as the Royal Bazaar or the Grand Bazaar of Isfahan, is located on the northern side of the Naghsh-e Jahan Square.

Qeysarie Bazaar, The Grand Bazaar of Isfahan

Qeysarie Bazaar, also known as the Royal Bazaar or the Grand Bazaar of Isfahan, is located on the northern side of the Naghsh-e Jahan Square. It is one of the first constructions built in the Naghsh-e Jahan Square, completed in 1605 AC.

The majestic entrance of the Qeysaie Bazaar (completed in 1617 AC) is decorated with eye-catching faience mosaic work. The spandrels are decorated with the image of a mythic creature: a being composed of a human head and a tiger body, shooting its dragon tail. Actually, the mythic symbol represents the ninth astrological, known as Sagittarius. Historians believe that Isfahan was founded in the ninth of the year, and that is why it appears on the spandrels at the top of the Qeysarie Gate.

In the middle of the portal, there are three frescos: the one on the west represents Shah Abbas hunting, the one in the middle shows Shah Abbas fighting the Uzbeks and the third one, on the east, demonstrates Europeans in the Safavid court. Below this frescos, there is a window which once was part of a Sharbat-sara (literally “syrup house”), where the king and his guests used to gather to drink and enjoy the eye-catching view of the Naghsh-e Jahan Square. Nowadays, this building has turned into a museum in which you can enjoy the works of modern Iranian artists. Also, it includes a tea-house, on the roof of the Bazaar, where you can sit, order a drink and enjoy the view of the square.

Flanking Qeysarie’s portal, there were two structures called Naqāreh-Khāneh (Timpani House), used to announce the time at dawn and sunset by playing trumpets and also timpani. Of these structures, there is no trace today.

The Qeysarie Bazaar itself includes a large number of roofed lanes, all lined with shops or hojrehs. At special intervals, usually four lanes meet and make a chahār-sūq. These chahār-sūqs are usually covered with a brick dome and function roughly as a crossroad or square, connecting different parts of the Qeysarie Bazaar together.

In addition to the main corridors, Qeysarie Bazaar is marked by different Saraas, Timchehs and Caravanserais which mostly hold workshops, storehouses and offices of some Bazaaris or merchants working in the bazaar. We strongly advise you to visit Timche Malek, a lavishly decorated Qajar-era building in the Bazaar.

All in all, the Qeysarie Bazaar makes an attraction which every traveler coming to Isfahan should make sure to visit. It is one of the biggest and most splendid bazaars in Iran, providing you with all types of Iran’s souvenirs. As you cross one lane, the fragrance of high-quality spices revitalizes your soul; another lane invites you to feast your eyes on the colorful designs of world-quality carpets; and in other lanes you will come across such beautiful handicrafts the examples of which you cannot find anywhere else in the world. Most important of all, the Qeysarie Bazaar is one of the best places where you can make connections with the local people and immerse yourself in the thousands-year-old culture of Isfahanian people.

Qeysarie Bazaar, also known as the Royal Bazaar or the Grand Bazaar of Isfahan, is located on the northern side of the Naghsh-e Jahan Square.

Local Food

Local cuisine

Gathering around a table in a cozy atmosphere, chating with your friends and fellow travelers while experiencing new flavors… this is also part of the trip.

In addition to the journey through space and time that you are about to live with us, you will also experience a sensory journey that will tantalize your taste buds.

What culinary wonders will you discover in Iran?

Spanning a vast geographic area and home to different ethnicities, each with their own culinary traditions handed down from generation to generation, Iran offers an astonishing variety of traditional dishes.

If you enjoy seafood and fish products, cities in southern or northern Iran offer a wide variety of different fishes as well as the renowned Iranian caviar. Do you have a preference for meat? Then you will feast on grilled meats, locally called kebab. The recipes are diverse and varied, depending on the regions, seasonings and marinades. As for the rice that accompanies most dishes, it can also be cooked in several forms and is most of the time delicately flavored with saffron or herbs. There is also a great diversity of stews, typically Iranian like Ghorme-sabzi, or Fesenjan whose flavors provided by local ingredients are unmatched. If you are a vegetarian, you will also find what you are looking for in salads, soups or stews.

We will give you a fantastic experience of all these amazing foods. Our expert guides will help you get acquainted not only with Persian cuisine, but also the culture associated with it.

You will have the possibility, if you wish, to spend an evening in an Iranian home, to discover the family cooking secrets. A warm moment of cultural sharing. An unforgettable experience!

Your Irandelle travel agency will make you discover the best tables, those where you eat the best, thus making you discover the culinary delights of the country and the associated traditions.

Tazieh, a religious Theater

It is a kind of traditional Iranian religious theater, performed on the occasion of the martyrdom of Hossein, grandson of the prophet Mohamed in Karbala in 681 AD.

These performances are intended to commemorate and share the pain of the drama, and the oppressions inflicted by Yazid, the son of Muawyia on the family of the Prophet.

Tazieh, a religious Theater

It is a kind of traditional Iranian religious theater, performed on the occasion of the martyrdom of Hossein, grandson of the prophet Mohamed in Karbala in 681 AD.

These performances are intended to commemorate and share the pain of the drama, and the oppressions inflicted by Yazid, the son of Muawyia on the family of the Prophet.

This style of performance originated in the Qajar era, in the 19th century, and is literally based on a tradition collected orally.

Some peculiarities that we find in each performance of this living scene:

– The spectacle sometimes lasts a whole day from morning until sunset or until the assassination of Hossein.

– All dialogue recounts the strong moments to the rhythm of litanies to sadden and make the spectators cry. Long texts sung in poetry are recited according to manuscripts kept by the actors.

– Normally the role of women is played by men veiled in black.

– The Imam and his companions (the oppressed) are dressed in green and the yazidi (the oppressors) in red.

– At midday, during prayer there is an intermission, lunch is provided for all the spectators, an ex-voto from generous donors.

– A whole orchestra of percussions and flutes accompany the show.

– An extra cavalry in charge of mounting a horse accompanied by music, turns around the stage on command.

– The staging is done live in full view of the spectators, there is no backstage.