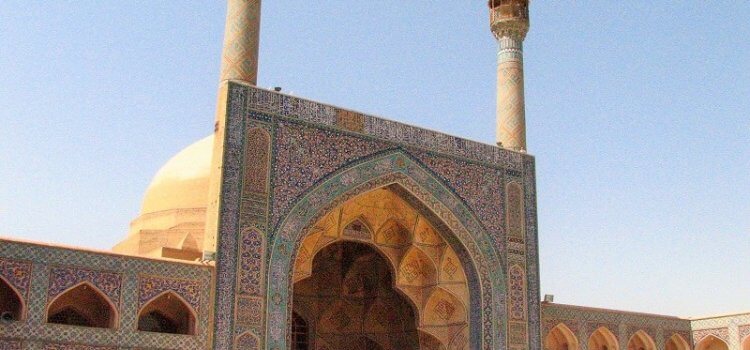

Jameh Mosque of Isfahan

The construction of Jameh Mosque in Isfahan last a millennium.

Jameh mosque of isfahan is one of the oldest mosque in iran.

It begins with Arab-style, and ends with a 4 Iwans plan, decoration from the simple brick-works to finely stylized mosaic patterns, the mosque has more things to say about the history of the city; its neighborhood with Jewish district and adjacent to Grand Bazar can offer much more attractions for the travelers in its surrounding.

Khaju Bridge

If you come to Isfahan and ask people about the tourist attractions in and around the city, you will surely be recommended to visit Khaju Bridge

The Only Bridge Decorated with Haft-Rangi Tiles in Iran

If you come to Isfahan and ask people about the tourist attractions in and around the city, you will surely be recommended to visit Khaju Bridge over and over again. But why?

Well, Khaju Bridge is a multi-purpose bridge built by the order of Safavid king, Shah Abbas II, about 350 years ago. This old but invincible bridge has won the heart of people of Isfahan for several different reasons. First of all, its beauty is exemplary, being the only bridge decorated with haft-Rangi tiles in Iran. From afar, it lies in front of you like a half-drown, charming Persian girl. Standing in one of its vaulted niches, it seems as if the bridge magically directs your eyes toward the most beautiful scenes in Isfahan.

Also, it is filled with positive vibe, energizing and mesmerizing people for hundreds of years. From the time of Shah Abbas II, Khaju bridge has been a place of celebrations, public meetings, public concerts and, generally speaking, a refuge from the burden of everyday life.

Now, let’s delve a bit more into architecture and history to appreciate as much as possible the beauties of Khaju Bridge.

The History of Khaju Bridge

Years before the Safavids choosing Isfahan as the seat of their power (at the beginning of 17th century), there was a bridge on the eastern bank of Zayandeh-Rood River, connecting the city to the road which led to the city of Shiraz. This 15th bridge was built by the order of Hasan Pasha or Hasan Beik, a Timurid governor, and so was known as Hasan Abad Bridge.

But about 200 hundred years later, the Safavid king Shah Abbas II decided to build a totally new bridge over the foundations of Hasan Abad Bridge. So, architects, masons and construction workers rolled their sleeves up and built a bridge which matched the burning desires and cravings of the king.

The author of the book “Ghesas al-Khaqani” (Kings’ Tales) tells the story of the inauguration of the bridge as follows: in the year 1650, after Nowruz (Persian New Year) vacations, Shah Abbas II ordered the inauguration of the bridge. Accordingly, the bridge was decorated, covered with flowers and lighted with numerous lamps. In addition, each one of its rooms was decorated by a certain dignitary. And, in this way, Khaju Bridge was opened to the public.

However, you should know that the bridge was first known as Pol-e Shahi (or Royal Bridge). Then, it became famous as Khaju Bridge. But, what does Khaju mean?

Khaju Bridge? What does Khaoo mean?

The word Khaju is derived from Khajeh, a title used for courtiers and those close to the royal family. Now, since these courtiers were living in a neighborhood close to the Royal Bridge, the bridge also came to be known as Khaju, although with a bit of phonological change.

The Architecture of Khaju Bridge

Khaju Bridge is 133 m long, 12 m wide and includes 23 arches. is a double-decker bridge. The upper storey includes a main passageway which was used by caravans and two covered corridors, on both right and left sides, for pedestrians. The lower part of the bridge was used only by pedestrians, as a rendezvous for friendly meetings and a center of recreation.

As mentioned before, Khaju Bridge served different function and purposes. Firstly, it was used as a dam to regulate the flow of water of the Zayandeh-rud. When the 21 lower sluices were blocked by wooden panels fitted into stone grooves, the level of water behind this man-made dam increased substantially. The surplus water gathered by this engineering trick was used to fill the underground reservoirs and to irrigate the gardens built along the banks of the river. Also, by closing sluice gates, an artificial lake was formed on the Western side of the bridge at the time of festivals. In this way, the river welcomed the many boats which sailed through it during various celebrations. Fireworks, and their reflection in the water, also enhanced the spectacle.

Now, lets go to the upper storey. As we have mentioned before, the false-arches on the inner side of the bridge are decorated with haft-rangi tiles, a unique feature not enjoyed by any other bridge in Iran. In the middle of the western and eastern sides of the bridge, there are two pavilions known as Shah-Neshin. Each one of these Shah-Neshins is comprised of a large room overlooking three balconies. All of these rooms and balconies are decorated with murals from the Qajar period, painted over those from the 17th century Safavid era.

Looking down on the stone foundations and the flowing water from these rooms gives one the impression of being on a boat sailing through the river. During a flood, the conical-shaped stone structures on the lower and upper storeys helped water pass through the bridge, and thus prevented any damage to the bridge itself.

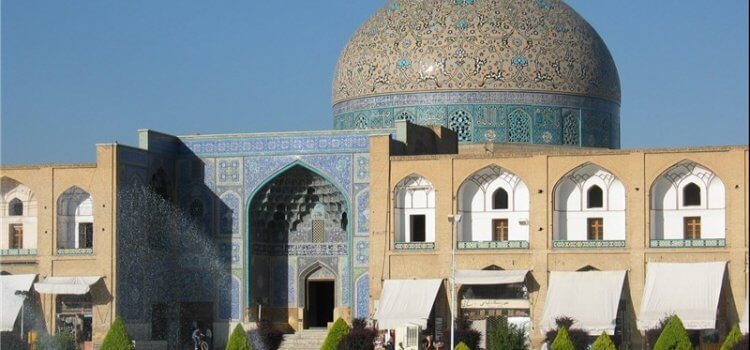

Jameh Abbasi Mosque (Imam Mosque)

On the Southern wing of the magnificent Naghsh-e Jahan Square, there stands a grand mosque, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which represents one of the greatest achievements of the Safavid period in terms of architecture, decorative arts and the social and religious role it played in its heyday. This unique marvel is nothing but Jame Abbasi Mosque, also known as Shah Mosque and Soltani (Royal) Mosque. After the Islamic Revolution of Iran (1978-79), following the new political sensibilities of the time, it was renamed Imam Mosque.

Shah Abbas Orders the Construction of Jame Abbasi Mosque

Eskandar Beik Turkaman, the great historian of Shah Abbas’ court, tells the story of the construction of Jame Abbasi Mosque as follows: At the beginning of this blessed year (that is, 1611) the astrologists determined the fortunate hour to construct a grand mosque which would be the pride of heaven and earth. And so, the king ordered the construction of the first congregational mosque built under Safavid royal patronage. Even as a sign of God’s approval, several marble mines were discovered nearby, hidden in the depth of earth where no human would have suspected their existence.

Therefore, the construction of Shah Mosque began on the Southern side of Naghsh-e Jahan Square. Actually, the positioning of the mosque was a very clever move. Being located just across Qeysaria Bazaar, it attracted large groups of people who were after their daily business in the bazaar. In addition, passing Ali-Qapu Palace and the theological school and mosque of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque assured people od Safavid protection and patronage. The construction of the mosque which began in 1611 ended in 1629.

However, there are inscriptions in the mosque which indicate several parts or decorations were added to the mosque during the reign of Shah Safi (1629-1642), Shah Abbas II (1632-1666) and Shah Soleyman (1648-1694).

What to See in Jameh Abbasi Mosque (Imam Mosque)

The massive Jameh Abbasi Mosque, covering an area about 19.000 square meters, is an architectural wonder with many details that would bewilder its visitors. In the rest of this article, we would introduce all the necessary details you need to know to fully appreciate the beauties of Jame Abbasi Mosque.

The Splendid Architecture of Jame Abbasi Mosque

The Portal

When you reach Jame Abbasi Mosque, before getting to the portal, you have to pass through a semi-circle pish-khan or forecourt. Flanking the eastern and western sides of the forecourt, there are two corridors containing shops and connected to Qeysarie Bazaar. In the middle of the pish-khan, there is a stone pond which used to be filled with water for the purpose of ablution. The walls surrounding the forecourt are decorated with false-arches, inscriptions, and haft-rangi (seven-color) tiles.

The portal itself is composed of different parts. It includes two goldasta minarets, each one rising as high as 42m. The minarets include decorations of spiral blue turquoise tiles and Bannai inscriptions. At the top of each minaret, there is a goldasta, a special space from which mo’azen calls people to prayer. However, since these goldastas overlooked the royal harem, they were never used during the Safavid period.

The main part of the portal is 27m high, embellished with haft-rangi tiles and faience mosaic. Around the portal, there is a large inscription representing a line from the Quran which reads as: “Do not stand in it ever! A mosque founded on God-wariness from the [very] first day is worthier that you stand in it [for prayer]. Therein are men who love to keep pure, and Allah loves those who keep pure.”

The niche composing the middle part of the portal is decorated with amazing honey-comb stalactites, giving the portal a stunning view. Below the stalactites, in the middle elevation and left and right sides, there are designs of three pairs of peacocks, representing god’s perfection as well as integrity and beauty.

Below this niche, in the middle of the portal, there are several important inscriptions. The largest one, running from East to West, states that Shah Abbas I built Jame Abbasi Mosque from the royal treasure (khāleseh) and dedicated it to the soul of his grandfather, Shah Tahmāsb. At the end of this inscription, you can find the name of the calligrapher, Ali-Reza abbasi, the chief librarian and the master calligrapher of Shah Abbas’ time, and also the date of the completion of the portal, 1616 AC.

Just under the inscription mentioned above, there is another smaller inscription written by Mohammad-Reza Imāmi which credits Moheb-Ali Beig Lala with supervision over the construction of the mosque. This same dignitary had joined the Shah by contributing to the endowments of the mosque from his own personal funds. The names of two architects are also associated with mosque: 1. Maestro Ali-Akbar Isfahani as the engineer of the mosque and, 2. Maestro Badi’-al-Zaman Tuni Yazdi, responsible for procuring the land and construction resources.

At the base of the portal, there exists two high-relief marble vases from which rises spiral turquoise tiles. The spiral tiles, on the one hand, symbolize Tuba tree of paradise, and on the other hand, draw the viewer’s eyes upward toward the apex and infinity.

The original doors of the portal (4 m by 1.7 m each) were of plane trees, covered with a thin layer of gold and silver and decorated with carvings and filigrees. Several lines of poetry are engraved around the door, the last one of them functioning as a chronogram. Based on this line, the gates were installed during the reign of Shah Safi (1629-1642).

A Great Engineering Dilemma Solved

Just like Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, the façade of Jame Abbasi Mosque had to remain flush with the southern side of Naghsh-e Jahan Square, while at the same time orienting its mihrab(s) (prayer niches) correctly toward Qilba or Mecca. And this created a quite difficult challenge for the visual effect of skewed internal axis, which would be magnified in the royal mosque. However, as Sunan Babaie argues: “the architects and patrons of the mosque exploited this very potential for theatrical visual impact by creating a crescendo of forms heaped from one side to the other; viewed from a distance in the Meydān, as would have been the case for most denizens busy in the public square, the eye of the beholder is lead from the open-armed portal composition with its massive pištāq and soaring goldasta minarets to increasingly volumetric and loftier units culminating with the pišṭāq-dome-minarets of the qebla wall. To the worshipper entering the mosque, the transition from the gorgeously tiled and moqarnas-covered ayvān on the Meydān side to the courtyard is mediated through a twisted passageway-cum-ayvān that serves also as the northern ayvān of the courtyard.”

And she continues: “This entrance complex corrects the alignment of the mosque by twisting the axis of approach, but it also provides a liminal space passage through which provides the worshipper the opportunity, visually and spatially mediated, to leave the mundane world behind before entering the sanctified space of the mosque.”

Upon Entering Jame Abbasi Mosque

As the visitor passes through the gate and enters the mosque, he or she finds him/herself in the vestibule of the mosque, with a roof covered with amazing moqarnas (stalactite) decorations. The vestibule is flanked by two corridors, covered with haft-rangi tiles whose densely floral and vegetal decorations are reminiscent of the mythic Persian gardens and the Paradise.

If you take the left corridor, before reaching the main courtyard, you will notice a small door on your left. Passing through this door, you will find yourself in a semi-dark space which is called Gāv-Chāh. In this part of the mosque, there is a quite large pond and above it, on a stone platform, there is water well. Since they used to draw water from these wells by cows, it is called Gav (cow) Chāh (well). The water drawn from the well filled the pond and was used for making ablutions or other sanitary purposes.

The Main Courtyard

Leaving the corridor, you will find yourself in the main courtyard of the mosque. Following the traditional plan of Iranian mosques, known as Chahar-iwany, the main courtyard is surrounded by four iwans or porches. Traditionally, each of these four porches were used in a specific season, providing prayers with suitably warm or cold praying rooms.

In the middle of the courtyard, there exists also a large stone pond which provided prayers with a further source of water for ablution.

By the way, the most important iwan or porch of the mosque is its southern one. Why? Well, the southern porch of the mosque is the one which is oriented toward Mecca, and therefore should be the most decorated and glorious one of the porches. And don’t forget that it is the general pattern in all the Iranian mosques because of the location of Qibla or Mecca.

The Glorious Iwan (porch) of Jame Abbasi Mosque

Well, the southern iwan of Jame Abbasi Mosque is flanked by a pair of minarets, each one soaring as high as 48 m. Through this porch, one can enter the main dome chamber of the mosque.

The main dome chamber is connected to two hypostyles, with amazingly decorated high-rise vaults supported by stone columns. Actually, the columns are made of blocks of stone joined together by molten-lead. This engineering trick increased the flexibility of the mosques and thus the mosques resistance against probable earthquakes.

The Amazing Dome Chamber of Jame Abbasi Mosque

The most significant part of the southern iwan; that is, its dome chamber, is 22.5 m in diameter hemmed by walls as thick as 4.5 m. These thick walls lay the foundation for the turquoise high-rise double-layered dome of the mosque, the one you can also see from outside of the mosque.

The 52m heart-shaped external dome is built over an internal 38m hyperbolical dome, with a 13 m gap between them.

One of the most interesting points about this dome is the way it reflects the sound. Stand under the dome (specially at its center marked by a black stone) and make a sound. You would be surprised how unbelievably it echoes.

The beauty of the mihrab (prayer niche) is enhanced by a marble pulpit with 12 stairs a few meters to its right.

The Theological Schools of Jameh Abbasi Mosque

On the east and west of Jameh Abbasi Mosque, there are two theological schools called Naserieh and soleymanieh. These schools were built during the Safavid period, but an inscription in Naserieh schools indicates that it was rebuilt during the Naser al-Din Shah Qajar and so its name.

In the Suleymanieh School, there is a sundial, indicating the exact time of noon all throughout the year. This unassuming engineering wonder, which looks like a simple step, was built by Sheikh Baha al-Din Mohammad Ameli, known as Sheikh Bahai, the Safavid polymath who was involved in the design of the whole monument.

Naghsh-e Jahan Square

Naghsh-e Jahan Square, also known as Shah Square and Imam Square, has been the heart of Isfahan for at least four centuries. Being the second largest square in the world after the Tian Amen Square in China, this UNESCO World Heritage site was, and still is, a thriving economic center, a lively cultural hub and a huge tourist attraction, welcoming tourists from both Iran and all over the world.

Actually, Naghsh-e Jahan Square is a true realization of the title it carries; that is, the Image of the World: the bazaars surrounding the square offer all sorts of commercial items, the delicate handicrafts showing off behind the shop windows make their visitors’ jaws drop, the lavishly decorated monuments provoke a gasp of amazement and its cozy atmosphere, marked by top-quality coffeeshops and traditional restaurants, provide both the locals and tourists with an intimate space ideal for friendly get-togethers and picnics.

But how did the splendid Naghsh-e Jahan Square come into being?

A Brief Look at the History of Naghsh-e Jahan Square

Naghsh-e Jahan Square, the symbol of the Safavid Dynasty

In 1546, Shah Tahmasb I (1514-1576) moved the capital of the Safavids from Tabriz to Qazvin to keep away from the constant threat of the Ottomans. Almost 46 years later, in the year 1592, Shah Abbas I (1571-1629) decided to transfer the capital of the Safavids once more, this time from Qazvin to Isfahan. According to historians, three main reasons motivated Shah Abbas the Great to make this decision: 1. the relative short distance from Isfahan to Bandar-e Abbas, a portal city intended to be a gateway to European countries and thus a means of Iran’s economic expansion, 2. the pleasant climate of Isfahan, and finally, 3. the geopolitical location of the city, distancing further the nucleus of the Safavid power from their archenemy, the Ottoman Turks.

Before the transference of the capital to Isfahan, people of Isfahan used to live in the Saljuq-built part of the city, composed of a number of distinct neighborhoods located around the Masjed-e Jameh (now referred to as Atiq Jameh Mosque) and the Saljuq square (today known as Imam Ali Square). The rest of area up to the Zayandeh Rood was occupied with a large piece of free and uninhabited land.

However, when Shah Abbas chose Isfahan as the seat of power, he and his advisers embarked on a construction campaign which lasted from 1590-1 to 1598, when Isfahan was officially announced as the capital of Iran. During these years, the uninhabited area between the Zayandeh-Rood and the old Saljuq town underwent a huge transformation, being adorned with numerous new gardens and monuments. Among these structures, Naghsh-e Jahan Square (Meydan-e Naghsh-e Jahan) and, Chahr Bāq boulevard, a magnificent tree-lined promenade, made the backbone of the Safavid capital city.

Actually, being in an intense political competition with the Ottoman Turks, Shah Abbas used all the resources available to him to build the Naghsh-e Jahan Square as majestically as possible, something which could rival the monuments built by the Ottomans and represent the power and grandeur of the Safavid dynasty.

Therefore, great masters such as Ali Akbar Isfahani and Mohammad Reza Isfahani were summoned to construct the huge Naghsh-e Jahan Square, measuring 512 m by 159 m. Functionally, the square was divided along its two main axes: Qeysarie Bazaar and Abbasi Mosque making the popular axis (north to south), Ali-Qapu palace and Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque forming the royal one (east to west).

As Jean Jardin (1643-1713), the French jeweler and traveler, describes the square, two hundred two-storey shops were built around square, each of them composed of two parts, one opening into the square and the other opening into the bazaar surrounding the square. On the second floor, there were also two-part rooms, one facing the square and the other connected to the corridors behind it. In front of the rooms opening into the square, there were small porticos guarded by plaster balustrades, painted red and green. Also, a stream of water was dug around the square, lined with plane trees to decorate them.

As a matter of fact, Naghsh-e Jahan Square served different functions during the Safavid period. Whenever people were called to prayer, they rushed to pray in Masjed Jame Abbasi. In the morning, businessmen and their customers took possession of the square. In the afternoon up to late at night, it was a site of leisure and entertainment. At the time of festivals and ceremonies, the decorated square welcomed the people of Isfahan for some hours of merry-making. And finally, on especial occasions, for example during Nowrouz (the Iranian New Year), the square turned into a field, occupied by polo players. The king and his guests were the special spectators of the match, watching it from the Ali-Qapu palace.

Naghsh-e Jahan Square during the Qajar Period

During the Qajar rule, the unfortunate square fell from grace and lost its splendor. For a while, it turned into a military barracks. The shops around the square became obsolete, the sumptuous monuments around the square lost their lavish decorations and the trees around the square, the ever-green symbols of life, were cut and disposed of.

Naghsh-e Jahan Square in the Pahlavi Era

In the 1930s, during the reign of Reza Shah, Darvaze Dolat square was expanded and two streets, Sepah and Hafez, were built as major entrances to the square. Sometime years later, a pool, measuring 30m ×80m, was built in the middle of the square. Almost at the same time, several flowerbeds came to decorate the Naghsh-e Jahan Square.

In 1935, the square was lit with electrical lamps, enabling people to enjoy the nights of the square as well. In addition, more than 100 disused shops were renovated, coming to life as handicraft shops. After Reza Shah’s reformations in the administrative system, several official buildings were added to the square, such as the two banks flanking the Qeysarieh gateway. Actually, the buildings surrounding the entrance of the bazaar belong mostly to the first Pahlavi era.

Sheikh Lotfollah

Sheikh Lotfollah was one of these doctors of religion who came from Lebanon to Iran

During the Safavid period, Iran was sandwiched between neighboring Sunni countries. Ottoman Turks, the most powerful of them all, were always threatening the boundaries of the Safavid Empire and a slight mistake meant losing the country. So, Safavid kings decided to establish Shiism as the dominant religion in Iran. As a result of these piolitical changes, a large number of Shiite scholars and faqihs migrated from Bahrain and Lebanon to Iran. Sheikh Lotfollah was one of these doctors of religion who came from Lebanon to Iran. First, he lodged in Mashhad but when Uzbecks attacked Mashhad, he moved to teach in Qazvin.

After a while, Shah Abbas invited Sheikh Lotfollah to Isfahan, married his daughter and built him a school and mosque in Naghsh-e Jahan Square, where he occupied the position of the Imam of the mosque and a teacher of religious matters until he died in 1623.

The Story of Allahverdi Khan

Allahverdi Khan (1560-1613) was originally a Christian born Georgian, from the Undiladze family. Like many other Georgians, he was captured as a prisoner of war during one of the Caucasian campaigns of Shah Tahmasp I.

Allahverdi Khan (1560-1613) was originally a Christian born Georgian, from the Undiladze family. Like many other Georgians, he was captured as a prisoner of war during one of the Caucasian campaigns of Shah Tahmasp I. Then, he converted to Islam and served as a soldier in the “Gholam” (servant) army, a special military force created by Shah Abbas I out of Christian captives. The purpose of this military unit was to curb the unlimited power of Qizilbash, the core of the Safavid military aristocracy.

However, this not much important servant gradually climbed to the top of ladder. First, he played an important role in the conspiracy against the powerful minister and king-maker Morshed Gholi Khan Ostajlou, whom Shah Abbas had condemned to death in secret. As a reward, he was appointed as the governor of Jorpadangan, a city near Isfahan, the capital of the Safavids. Soon after, he was chosen as the commander-in-chief of Gholam military, thus becoming one of the five principal officers in the Safavid administration by 1595/6. In the same year, he was designated as the governor of Fars, an act that made him the first gholam to attain equal status with the Qizilbash amirs.

During his life, Allah Verdi Khan commanded the Safavid army in many important battles. For example, the Battle of Sufiyan, where the Safavids devastated the army of Ottoman invaders.

Allah Verdi Khan had gained so much respect from Shah Abbas that when he died, the king personally accompanied his bier to the place where the corpse was ritually washed and prepared for burial. He was buried in a magnificent in Mashhad, the holiest city of Iran, beside the tomb of Imam Reza.

In his lifetime, Allah Verdi Khan patronized the construction a number of monuments and charitable foundations. Apart from Si-o-Se Pol, his legacy includes a large double dam near Sarab; a fortification around a village in Fars; the qeysarie bazaar, or royal market, of Lar; a magnificent mansion near Nahavand for Abbas I; and the theological school of Khan in Shiraz.

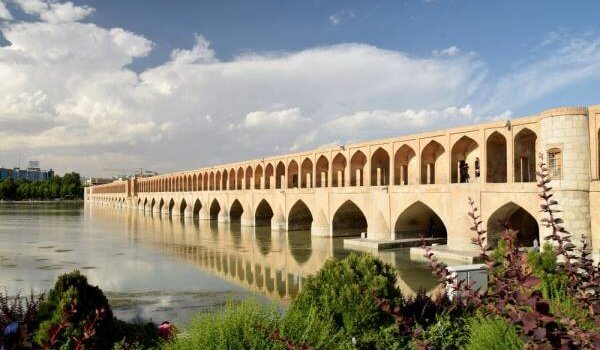

Siose Pol: A Unique Bridge and Symbol of Isfahan

During the years 1592-98, Shah Abbas I (1571-1629) launched a construction campaign in Isfahan to move the capital of the Safavid dynasty from Qazvin to Isfahan

Siose Pol: A Unique Bridge and Symbol of Isfahan

During the years 1592-98, Shah Abbas I (1571-1629) launched a construction campaign in Isfahan to move the capital of the Safavid dynasty from Qazvin to Isfahan. During this campaign, Shah Abbas and many other rich dignitaries and businessmen patronized the building of new monuments in Isfahan.

One of the main sites around which a lot of construction took place was Zayandeh Rud (Zayandeh River), the vital heart of the city and one of the main reasons Shah Abbas chose Isfahan as his capital. On the Southern side of Zayande Rud, Shah Abbas I built his favorite promenade, Chahar-Bagh-e Payeen. On the Northern side of the river, there was a complex of gardens, Sa’adat Abad, which were connected together via another promenade called Chahar-Bagh-e Bālā. To connect these two boulevards, the construction of a new bridge became necessary.

To build the bridge, Allah Verdi Khan, the Georgian commander-in-chief of Shah Abbas’ army, volunteered to pay its costs. The construction of the bridge began in 1599 and continued up to 1602.

Some Confusing Points about the Name of the Bridge Made Clear

Eskandar Beik Turkman, the great historian during the reign of Shah Abbas, refers to the bridge as Pol-e Chehel Cheshmeh. But why Chehl-Cgheshme? In Farsi, pol means bridge, chehel means forty and cheshmeh, as used here, refers to the false arches flanking the upper side of the bridge. So, at the time of its construction, the bridge had forty niches along each of its sides, and so was called Chehel-Cheshmeh.

At the same time, it was also called Pol-e Allahverdi Khan or Allahverdi Khan bridge, bearing the name of the man who contributed a large sum of money for its construction.

Nowadays, there are 33 arches along each side of the bridge, and therefore it is called Si-o-Se Pol.

There is just one point to remember. Do not call the bridge “Si-o-Se Pol bridge”! It is like saying “33 bridge bridge.” The best name to commit to your memory is “Si-o-Se Pol.” Just say it and all the locals would direct you to this bridge.

The Architecture of SioSe Pol

An architectural masterpiece by maestro Hossein Banna Isfahani, SioSe Pol is295 meter long and 14.75 meter wide. No wonder, its extreme length makes SioSe Pol one of the largest bridges in Iran.

Occupying the widest part of the Zayandeh Rud where we have the shallowest depth of water, the bridge is built of stone, Saruj, plaster, and brick. This choice of material ensures that the bridge remains stable under high pressure and exposure to moisture.

Si-o-Se Pol can be divided into two parts: the upper part and the lower part. The upper part includes a main passageway which is flanked by two corridors decorated with false arches. The passageway was used by people who transferred with beasts of burden and the corridors by pedestrians. People also used to meet and sit or stand in the niches under the false arches to enjoy the scenery and take pleasure in the various celebrations held around the bridge.

The lower part of the bridge includes 25 rooms of various sizes. During hot summers, the king and his court used to lodge in these room and enjoy the cool breeze which wafted in through the open windows.

Ceremonies Held at SioSe Pol

During Shah Abbas reign, people used to celebrate Nowruz (Persian New Year) for three to seven days at this bridge. During Nowruz, the bridge was decorated with numerous lights, turning it into a shining spot. Also, Shah Abbas sometimes ordered the Golrizan ceremony over the bridge, where the path of Shah Abbas and his entourage was covered with flowers cast by people.

In addition, the bridge welcomed people to celebrate a water ceremony called Ab-Pashan. This celebration was held annually on 13th of July, when people splashed each other with water and danced gleefully. The king, noble men, politicians, poets and other notables also attended the ceremony.

Another Celebration held at SioSe Pol was Khaj-Shuyan, a ceremony in memory of Jesus baptism. Christians believe that the water becomes pure and sacred on this day, so they gather around sources of water and swim in them to purge themselves of worldly filth. Khaj-Shuyan Celebration was held by Christian Armenians living outside Isfahan in New Julfa neighborhood.

The Best Time to Visit SioSe Pol

Although SioSe retains its beauty all throughout the day, we suggest that you visit the bridge at sunset. Its beauty would mesmerize you!

What to do at SioSe Pol?

Well, if you are tired of everyday burdens of life, you can go to SioSe Pol to have a long walk and let off steam. Also, you can mix with the locals in the evening and immerse yourself in the joys of finding new friends from a totally different culture. In the past, there some tea houses around the bridge, but it is some years that they have been closed off.

On the northern side of the bridge, there are some shopping malls which you can visit. On the Southern side of bridge, there is a famous ice-cream shop known as Bastani-ye Pol. You can go there and enjoy ice-creams of different flavors.

A little further up, there is another shop which make magic with pomegranate. Their products include ice-cream with pomegranate, lavashak and all sorts of sour and pungent delicacies which make your mouth water.

Spoiler

Due to dire effects of climate change, the Zayaznde Rud river has dried up and so the bridges and parks around the river are a little bit less splendid than their glorious old days.

Zayandeh Rud The Throbbing Heart of Isfahan

Zayandeh Rud, alternatively spelled as Zayande Rud or Zayande(h) Rood, is one of the most important rivers of Iran

Zayandeh Rud, alternatively spelled as Zayande Rud or Zayande(h) Rood, is one of the most important rivers of Iran, irrigating the lands located in the center of Iranian plateau. The river’s origin is in Kuhrang, a part of the Zard Kuh Bakhtiari Mountain range, where it flows east before disappearing in Gavkhuni Marshland. On its meandering way, it travels a distance of about 420 kilometers. At Shurab Village in the Tange Gazi district, several springs and rivers (Dimeh, Abzari, Chamdar, Abkhorbe and Na’leshkanan) join the flowing stream of water, making what is from now on called Zayande Rud or the life-giving River. Soon, another branch streaming from Kuhrang joins Zayande Rud. Furthermore, after Tange Gazi, three other rivers come to contribute to Zayande Rud: Kagunag, Khersanak and Plaskan. After Zayande Rud Dam Lake, no other sources of water contribute to the river.

Over the history, 13 bridges were built on Zayandeh Rud: 1. Evergan Bridge, 2. Zaman Khan Bridge, 3. Kalleh Bridge, 4. Baba Mahmud Bridge, 5. Falavarjan Bridge, 6. Marnan Bridge, 7. Si-o-Se Pol, 8. Juie Bridge, 9. Khaju Bridge, 10. Shahrestan Bridge, 11. Chum Bridge, 12. Soroush Azaran Bridge, and 13. Varzaneh Bridge.

Ali Qapu Palace

Ali-Qapu Palace is another gem tourists should make sure to visit while they are in Isfahan. Ali-Qapu palace is located on the west wing of Naghsh-e Jahan Square, in front of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque.

Ali-Qapu Palace is another gem tourists should make sure to visit while they are in Isfahan. Ali-Qapu palace is located on the west wing of Naghsh-e Jahan Square, in front of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque.

During the Safavid period, Ali Qapu Palace served different purposes: 1. it made an intimate relationship between the royal court and the common people coming and going in the square; 2. it functioned as the entrance to the complex of royal palaces behind Naghsh-e Jahan Square.; 3. it also functioned as an official office where the royal court met and solved the problems of the country.

Before the establishment of the new Safavid square which was originally called Meydan-e Shah (Shah Square), its site was almost occupied by an older 14th-century Timurid garden known as Naghsh-e Jahan. From the time of Shah Ismail, the area had both a meydan (square) and a palace called Dowlat-Khaneh (literally The House of the Government).

When Shah Abbas’ construction campaign began in Isfahan (1592-1598), he ordered the building of the five-storey Ali-Qapu Palace at the place of the older Dowlat-Khaneh. When the added parts were completed, the first floor was also transformed to match the rest of the building. It is interesting to know that Eskandarbeig Turkman, the historian of Shah Abbas’ court, refers to Ali Qapu Palace as dargah-e panj tabaqe, or (the gateway of the five-storey building).

As P.P.Soucek argues, the name Ali Qapu gained currency after the 1643-44 addition of gateway and Talar. It is believed that the doors of the gateway were transferred from the mausoleum of Imam Ali, the first Imam of the Shia Muslims, in Najaf (now in Iraq) to Isfahan and installed at the gate of the palace. From this time onward, the mansion came to be known as Ali Qapu or the “lofty door”.

When you pass the gate of Ali Qapu, you will enter an octagonal vestibule known as Hasht Behesht (or eight paradises). This part of palace is covered with an amazingly decorated dome, flanked by guards’ rooms and certain offices.

In front of you, there is a passageway, referred to as the royal passageway, which led to the palaces behind the Ali Qapu. Just after the vestibule, on your left, there is small a door which you should enter and take the steep stairs leading to the different floors and rooms of the Safavid mansion.

Generally, each floor of Ali-Qapu Palace includes a music room, a royal chamber and several banqueting rooms. All these rooms were centered around a large room, serving as the reception hall. Obviously, the king used to receive his high-ranking guests in these rooms.

To boast the grandeur of the court, all the 52 rooms of Ali Qapu Palace were decorated as majestically as possible: very delicate and highly priced rugs covered parts of the walls, while other parts were painted with incredibly beautiful frescos, representing a balanced, harmonious combination of floral designs, birds and European scenes. The curtains hung over the windows were of gold and silk fabric.

Following the steps takes you to the talar or the columned balcony of Ali Qapu Palace, built by the order of Shah Abbas II in 1648. This one of a type balcony, masterminded by the grand vizier of the king Saro Taqi, includes 18 columns, each one a 10-meter high trunk of a single plane tree. These 18 columns support a double-layered ceiling, embellished with fine inlaid work and frescos. In the middle of the terrace, there is a marble pond, its surface covered with copper. The king and his guests used to sit in this balcony while listening to the melodious flow of water in the pond and being entertained by celebrations, marches, local plays and even games of polo in the Naghsh-e Jahan Square below. And now that you have reached this royal balcony, we bet you would enjoy one of the most beautiful scenes you have ever seen in your life, a breath-taking panoramic view of the Naghsh-e Jahan Square.

Behind the columned terrace, there is Shah Abbas’ throne hall, used to receive royal guests. In comparison with other rooms, it is much larger, decorated with delicate stucco work, called lāyeh-chini, and fine frescos representing scenes similar to paintings in other rooms. These paintings were the work of Reza Abbasi, the great Safavid painter, and his talented students.

There is an interesting point you should know about this room. If you look up, you will see the upper part of the reception hall surrounded by a series of small windows. These rooms hosted the women of harem, where they gathered to partly enjoy the celebrations held in the reception hall by peeping through the windows.

The small balcony at the back of the throne hall overlooks a politico-religious monument called Tohid Khaneh. It is a single story, twelve-sided building reflecting the Shiites’ belief in the twelve scared Imams. The balcony also houses two narrow spiral staircases of 92 steps, taking you to the highest and most beautiful floor of Ali Qapu Palace, known as the Music Hall.

The Music Hall is also a late addition from the time of Shah Abbas II. It is decorated lavishly with the most beautiful patterns and fretwork stalactites, which are made of hollow pendentives of 20 different patterns. The reason this room is called Music Hall is because of the acoustic properties of these pendentives, which make this hall the most suitable place for performing music. The central part of the hall is cross-shaped, with an astonishingly decorated ceiling bearing stalactite squares transforming into squares. Staying in this room for a while works magic. Immerse yourself in the beauties of this hall and open your ears up to the centuries of music played here, the world will turn into a heavenly place.

Chehel Sotoun Palace

In a poem honoring the construction of the Chehel Sotoun (fourty columned) palace by the Safavid king Shah Abbas Il, Säéb Tabrizi describes the palace as the fairest of all monuments in the world.

In a poem honoring the construction of the Chehel Sotoun (fourty columned) palace by the Safavid king Shah Abbas Il, Säéb Tabrizi describes the palace as the fairest of all monuments in the world. And the description is well-deserved: the play of sun, water and mirrors, the green coolness of shadows spread across earth by tall plane trees, dazzling paintings, magnificently decorated rooms and a world of memories from the past, legendary kings all combine to make up the essence of the palace-museum of Chehel Sotoun. Read on to learn more about this gem — and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

A Brief History of Chehel Sotoun Palace

Ample water resources and its location at the heart of Iran – far removed from the influence of the Ottomans, not to mention in a privileged position vis-å-vis the Persian Gulf – made Isfahan an ideal city for Shah Abbäs to declare his capital in 1598, according to Michel M. Mazzaoui’s book on Safavid History. Yet, even before this move, a series of building campaigns, which lasted for eight years, were inaugurated in Isfahan in 1590/1 of iron will and passionate work. One of the areas which underwent construction and renewal during this period was the royal precinct of Isfahan, Extending from the Naqsh-e Jahän (image of the world) square to the Chahar Baq (four gardens) promenade. The royal precinct included the vast garden of Naqsh-e Jahän which formed the basis of the Chehel Sotoun garden and palace,

After the unstable reign of Mohammad Khodä-bandeh, Iran saw the emergence of a sharp strategist who was to bring great changes to Iran: Shah Abbäs the Great. One of Shah Abbās’ passions – during his fervent building campaigns in Isfahan – was to build gardens; a passion which would associate him with the great Achaemenid emperors and re-enforce his image as the king of Iran.

At the time, the garden of Naqsh-e Jahän was used to host audiences and royal ceremonies. To accomplish these tasks, Shāh Abbās built a pavilion, surrounded by a number of small rooms in the middle of Bāq-e Naqsh-e Jahān (Naqsh-e Jahän Garden).

The royal ceremonies had by then turned into political and cultural symbols that represented the authority of the king and, as a consequence, these changes necessitated a renewal of form in designing the royal palaces: spacious palaces were needed to hold both the king’s court and his lofty ceremonies. The key to solving this problem was a man known as Sārū Taqi (Mirza Mohammad Taqi), the grand vizier of both Shah Safi and Shih Abbās II.

Sārü Taqi combined the idea of the wooden, columned talars (porticos) of monuments in Mazandaran with the halls and palaces existing in Isfahan to solve the issue of much needed larger spaces.

With the advent of Shah Abbas II’s rule, Naghsh-e Jahan Garden underwent major reconstructions. Preserving Shah Abbas I’s pavilion as the nucleus of the new building, Shāh Abbäs Il added two porticos on the northern and southern sides of the pavilion, an adjacent wing with a large iwan (terrace) on the east and a spacious columned at the front, according to Ingeborg Lugchey-Schmeisser. After the addition of columns, the garden of Naghsh-e Jahän and the palace inside it became known as Chehel Sotoun.

In 1668, the splendid coronation of Shih Soleyman was held in the Chehel Sotoun palace. However, disaster befell the palace after the auspicious coronation: during the month of Ramadan 1707, the palace was lit with numerous lamps to commemorate the religious ritual of Shab-e Qadr. The ceremony went on normally until a curtain caught fire and the flames began to devour the wooden talar. The servants rushed to inform Shah Soltän Hosein, but he replied: “let it be! It is a misfortune that should pass.” And so, the talar burnt to ashes.

Sometime later, Shah Soltan Hossein rebuilt the talar, but darker days were vet to come. In 1722, Afghan troops arrived at Isfahan and besieged the city. After several months of hardship and famine, Shah Soltän Hosein surrendered Isfahan to the Afghans. When Mahmoud Hotaki, the leader of the Afghans, entered Isfahan he went to the Chehel Sotoun Palace, destroyed the royal throne and married the daughter of Shāh Soltān Hossein.

The story of Chehel Sotoun palace became complicated during the Qajar period in the 19th century. For some time, it was used as a workshop for the tent-makers of Masoud Mirza Zell-e Soitan, the governor of Isfahan. Later, just as his son Sārem al-Dowleh Akbar Mirza was about to destroy the whole place – he had even removed some plinths from their place — the Constitutional Revolution took place and the palace was redeemed from its fate, according to Jalal al-Din Homai’s History of Isfahan. Between the years 1906-08, known as the first period of the Constitutional Revolution, the palace was used by the Sacred National Council of Isfahan and therefore became the most important center of power in the city.

Fred Richards (1878-1932), an English painter, described the garden during the first days of Reza Shih pahlavi. He wrote: “the garden has lost its previous greenness for lack of care and nothing has survived but the trees and the pool.” As available documents show, the garden was being used as a military base at the time. Then. in 1931, the municipality of Isfahan, or Baladiye, took possession of the palace. Later, the Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, Rome (IsMEO), came to Isfahan and renovated the palace based on its old photographs. In 1948, the museum of Chehel Sotoun palace was inaugurated. After eighteen years, in order to undertake further renovations, items in the museum were moved to the banquet hall. They were displayed in this hall for five years after which they were transferred to storerooms, and no longer displayed.

Architecture

Chehel Sotoun Palace is situated to the east of Ostandari Avenue and south of Sepah Street. The garden has three entrances: one on the northern side, one on the western side and its old, main one on the eastern side. The eastern gate, in Ostandari Street, is once again being used as the entrance to the garden. This recessed entrance is flanked by two buildings: Talar-e Teimuri and Jobbeh khäneh.

Behind th’S gate lies the garden and palace ofChehel Sotoun_ The garden is rectangular with an area of about 67,000 square meters. Stretching from east to west, the garden is divided into two halves: one to the north and one to the south. On the eastern side of the garden, fronting the pavilion, there is a long pool, 110 m long and 16 m wide. At each of the four corners of the pool, four statues are displayed; each one a figural group including four angels (symbols of protection) and four lions’ heads (symbols of power), which were brought from the Safavid Sar-Pooshideh (roofed) Pavilion. This pool, as Ingeborg Luschey-Schmeisser explains: “helps to integrate the palace with the garden and extends it visually.”

The pavilion is situated in the western third of the garden and stands on a rectangular stone platform, The talar includes three rows of six polygonal columns, each made of a plane-tree trunk with a height of 13.05 m. These columns are adorned with muqarnas (stalactite) capitals and stone bases. In the 17th century, the traveler Jean Chardin described the columns as ‘turned and gilded’ and the explorer Engelbert Kaernpfer reported them as blue and gold, but the Carmelite bishop Barnabas told of the shafts as “covered with pieces of looking-glass” in the 18th century.

The eighteen columns of the talar and the two columns of the Shah-neshin (king’s room) make up twenty columns together. When these twenty columns are reflected in the long pool in front of the pavilion, the number of columns appears to be forty. It is believed that this is why the palace and garden bear the title “Chehel Sotoun” that means “forty Columned’. The true reason, however, is that forty is both a sacred number and a number that signifies abundance in Persian culture, and that is why Safavid kings chose this appellation for their royal palace and garden.

Two further columns, two wooden balustrades and a slight elevation separate the columned talar (from the adjacent hall, which is sometimes called the Mirror Hall, or Shah-neshin). The hall is formed by two flanking rooms and a further elevation, which divides it in two parts. In the middle of the first half of the Shah-neshin, there used to be a three-tiered marble pool. The wooden ceiling, above the previous pool, is decorated with a chequered panel, inlaid with mirrors of various sizes. The second half of the Shah-neshin houses the throne platform. The ceiling above the throne platform displays decorative muqarnas, filled with mirror work are attributed to this fresco outlined in fine golden lines. From a dado, half way up, the walls are also covered with mirror work.

The banquet Hall is a spacious rectangular room, flanked by two-storey rooms at each corner. The most striking feature of this wall is its wall-paintings, which narrate stories of power, glory, humiliation and love.

To the west of Banquet Hall, there is portico identical to the Shah-neshin on the eastern side of the hall. The portico is embellished with muqarnas decorations and delicate stucco work. Fine miniatures adorn this iwan and its flanking rooms, too.

Wall-Paintings

The walls of the banquet hall are divided into three zones: from the ground up to an eye-level dado: the main decorated zone above this; and, finally, the upper zone. The most eye-catching wall paintings in this hall are the four frescos and the two Ghahve khanei (coffee-house) paintings in the upper zone.

Below these paintings, in the main decorated zone, there is a band of other smaller wall paintings. Representing courtly picnics with few figures, these paintings date to the middle of 17th century. As Sussan Babaie points out: “there must have been a dado faced with painted walls, almost overwhelmed by the powerful paintings of the wall niches.”

The rooms flanking the banquet hall are also covered with frescos from the Safavid era; these were discovered under a coat of whitewash, which was applied to them in the Qäjär period. In these rooms, only two paintings represent landscapes, birds, trees and deer. In the northeastern room, off the banquet hall, there are some frescos representing Shah Abbas and his I and his retinue in the open air and in other courtly settings, celebrating and enjoying themselves. In a symmetrical room on the other side of the hall, which is called Chahar Shanbeh Suri (an ancient Iranian feast celebrating the last Wednesday before Nowruz), there is a fresco which gives its name to the room.

Two stories are attributed to this fresco: one story claims that it depicts the wedding ceremony of Reza Qoli, son of Nader Shah Afshar, to an Indian girl; the other connects it the painting to a tragic historical event in which a girl set herself on fire after the siege of Bukhara by Shah Abbas II. There are also scenes inspired by Persian love poetry: Khosrow and Shirin by Nizami Ganjavi and Yusof and Zoleikha.

In the Garden of Chehl Sotoun there are further other objects from the Safavid period; such as portals, inscriptions and tile work from the Qotbiyeh, darb-e Jubareh, Pir-e Pinehduz and Darb-Kooshk mosques, installed on the Western and Southern walls of the garden.